It is a common military adage that "generals are always prepared to fight the last war," meaning leaders often focus on past challenges rather than adapting to new realities. Today, a similar mindset may be shaping economic policy and investor decisions. While public debate centers on inflation – currently near 3% in the U.S.1 – the more significant challenge for advanced economies is the risk of structural deflation.

Two powerful forces are driving this shift: rapid technological automation and demographic aging. Increasing implementation of artificial intelligence expands productive capacity while reducing labor demand. Also, as populations grow older and consume less, the traditional balance between supply, demand, and price is fundamentally changing. These trends are expected to push inflation persistently downward. Japan’s decades-long struggle with deflation shows how difficult it is to reverse these dynamics once they take hold. More recently, China has exhibited similar patterns, with deflation emerging from excess supply and weakening consumption.2 The real economic battle ahead may not be inflation, but the persistent drag of deflation.

AUTOMATION, AI, AND EXPANDING SUPPLY

Rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and automation are reshaping labor markets. This is not completely new, since technologies of the past have led to economies being able to produce more with less, but the advances around us may be the most dramatic of our lives. Tasks once performed by humans – coding, customer service, logistics, manufacturing, and professional services such as legal and accounting– are increasingly automated. Automation increases productive capacity by substituting technology for labor, which lowers marginal costs, improves efficiency, and enables continuous operation.

Beyond making workers more productive, these new technologies are likely to reduce labor demand. This can lead to lower wages and fewer jobs, either of which reduce consumption. When supply expands faster than demand, prices fall. This is classic supply‑demand dynamics applied to a technologically transformed economy.

DEMOGRAPHIC AGING AND DECLINING DEMAND

The swift changes to labor productivity from AI and automation coincide with a slower-paced, long term deflationary force: demographics. The United States, Europe, and East Asia are all aging rapidly, with Japan furthest along this path.

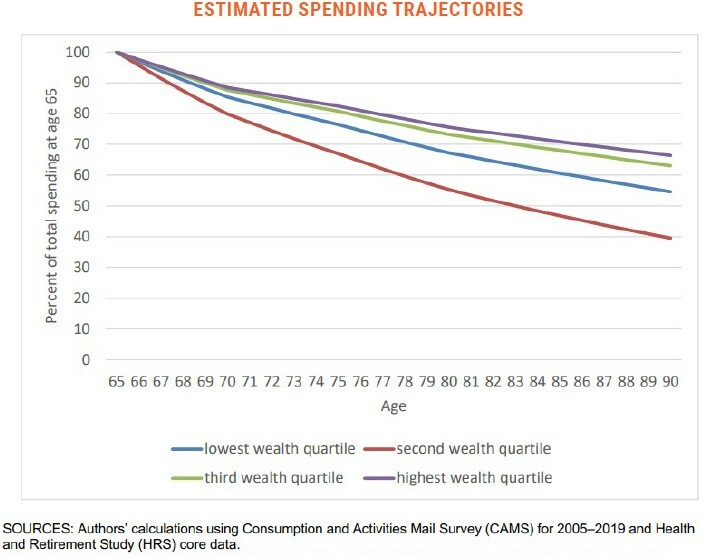

As populations age, consumption patterns change in predictable ways. Empirical research shows that spending declines sharply after age 65. A RAND Corporation analysis finds that real spending falls steadily after age 65 at annual rates of 1.7% to 2.4%, even among high‑wealth households.3 The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that households age 75 and older spend substantially less across nearly all categories except healthcare, confirming a broad decline in discretionary consumption.4

THE AGING OF THE US POPULATION

The United States is experiencing a profound demographic shift as the baby boom generation moves into retirement. This year, the leading edge of the baby boomers will be 80 years old, and all of that generation will be over 65 by 2030.5 To put this in perspective, S&P Global projects that one in five Americans will be retirement‑age by the end of the decade, with the 65+ population expected to reach 71.6 million, or 20.7% of the population.6

The number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to further rise to 82 million by 2050, increasing their share of the population to 23%.5 S&P Global notes that this aging trend will place sustained pressure on consumption patterns and long‑term economic growth as the dependency ratio rises and the working‑age population shrinks relative to retirees. These demographic realities mirror the earlier trajectory of Japan and reinforce the structural decline in aggregate demand that accompanies an aging population.

THE DEFLATIONARY FEEDBACK LOOP

Deflation is not only a mechanical outcome of supply and demand; it is also a psychological and behavioral phenomenon. When consumers expect lower prices in the future, they delay purchases. This reduces current demand, pushing prices down further and reinforcing expectations. Producers respond by cutting investment, reducing wages, and automating further to maintain margins. These actions deepen the cycle.

Japan’s experience over the past 30 years demonstrates how persistent deflation can become. Despite massive fiscal stimulus, quantitative easing, and negative interest rates, Japan has struggled to generate sustained inflation. Once deflationary expectations become embedded, traditional policy tools lose effectiveness.

China now shows signs of entering a similar pattern. Over the past several years, the country has experienced persistent producer‑price deflation and periods of negative consumer‑price inflation driven by excess industrial capacity and weakening domestic consumption. Producer prices have fallen year‑over‑year for nearly three consecutive years reflecting structural imbalances in supply and demand.2 Consumer prices have also slipped into negative territory at times, with analysts warning that deflationary pressures remain entrenched despite stimulus efforts. These trends highlight how large, developed economies can face prolonged deflation when consumption slows and supply remains excessive.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS AND REINVESTMENT RATE RISK

A deflationary or chronically-low interest rate environment poses significant challenges for investors, particularly those relying on fixed‑income instruments. As interest rates fall, maturing bonds must be reinvested at lower yields, reducing portfolio income. This reinvestment‑rate risk is especially acute for retirees, pensions, and endowments that depend on predictable cash flows. We had a glimpse of this problem just a decade ago when Japan and most of Europe experienced negative interest rates on government debt and the US experienced rates half or less of what they are now.

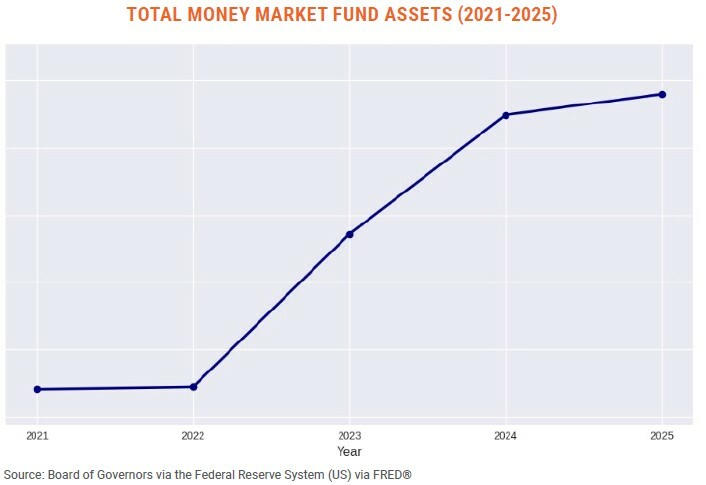

Several strategies can help mitigate this risk. Extending duration allows investors to lock in yields for longer periods, though it increases sensitivity to rate changes. Barbell strategies—combining long‑duration bonds with short‑duration instruments—can balance stability with liquidity and optionality. Money market funds, which have seen strong inflows over the past few years, are most susceptible to the “lost earnings power” of lower interest rates. Investors should also avoid the allure of higher yielding callable bonds, which expose them to reinvestment at lower yields precisely when rates fall; instead, they should emphasize longer‑term, high‑quality, non‑callable bonds to preserve income stability. US Treasury bonds fit the bill. High‑quality equities with durable dividends may also offer resilience when bond yields are compressed.

CONCLUSION

Demographic aging and rapid AI-driven automation are reshaping the global economy in ways that point potentially toward a deflationary future. As demand weakens and supply expands, prices may fall persistently, and expectations of deflation may become entrenched. Japan’s experience shows how difficult it is to reverse these dynamics once they take hold. China’s recent deflationary pressures underscore that even large, dynamic economies are vulnerable when consumption slows and supply remains excessive. Policymakers and investors alike must prepare for a world where low inflation, low interest rates, and reinvestment‑rate risk are defining features of the economic landscape.

SOURCES

INVEST SMARTER

Call (585) 485-0135 to discuss how a factor-based approach could pay off for you.